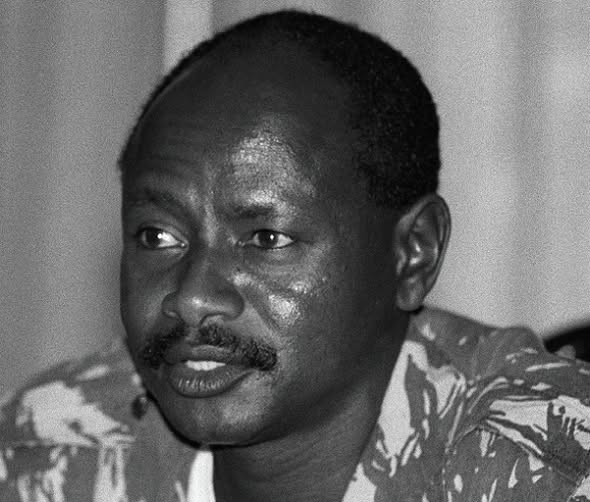

Decades before becoming one of Africa’s longest-serving presidents, Yoweri Kaguta Museveni repeatedly argued that the continent’s deepest crisis lay not with its people, but with leaders who cling to power, abuse authority and undermine the sovereignty of citizens.

“Africa’s problem is leaders who do not want to leave power,” Museveni declared in his now-famous January 29, 1986, inaugural address, shortly after the National Resistance Army (NRA) captured Kampala. “The problem of Africa in general and Uganda in particular is not the people but the leaders who want to overstay in power.”

The statement has since become one of the most cited lines in Uganda’s political history, often juxtaposed against Museveni’s own extended tenure in office.

Early warnings on leadership and power

Museveni’s critique of African leadership predates his rise to power. In a Weekly Topic publication dated June 6, 1980, he lamented the scarcity of ethical leadership in the country, stating bluntly:

“Cleanliness in leadership is one of the rarest commodities in Uganda.”

At the time, Museveni was leading the Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM) and campaigning against what he later described as a fraudulent electoral process that returned Milton Obote to power. Just months later, he launched the armed rebellion that ignited the 1981–1986 bush war.

His insistence on popular sovereignty was also explicit. Speaking at a press conference in Nairobi, Kenya, on December 18, 1985, Museveni said:

“The rights of the people are sovereign. The people are the sovereign power in the land. Anybody who does not recognise that ought not to be in power.”

Justifying armed struggle

Museveni consistently framed violence against authoritarian regimes as a last resort forced by abuse of power. In a speech at Ishaka in Bushenyi District, reported by Uganda Times on July 16, 1979, he defended armed resistance against Idi Amin’s rule.

“A government that subjects its citizens to humiliation and desperate solutions is not worth the name and should hence be removed,” Museveni said. “It was the violation of this cardinal principle by [Idi] Amin that forced Ugandans to take to arms to liberate their motherland.”

These views later formed the ideological backbone of the National Resistance Movement (NRM), crystallised in its Ten-Point Programme, which promised democracy, security, an end to corruption and the restoration of social services.

From ideals to power

When Museveni took power in 1986 at the age of 41, he pledged what he called a “fundamental change” rather than a “mere change of guards.” His inaugural speech strongly condemned leaders who ruled through fear and violence.

“No one should think that what is happening today is a mere change of guard,” he said. “This is a fundamental change in the politics of our country.”

Yet, nearly four decades later, Museveni remains in power, often defending his rule on the basis of stability, security and economic growth. This is the basis of his 2026 campaign slogan, “Protecting The Gains”.

In a more recent address to supporters in Lango, Museveni warned against what he described as political ingratitude and reckless opposition to the NRM’s record.

“And all these people who are challenging the NRM, nobody has contributed anything to that peace,” he said. “You cannot go and play around with Uganda. Uganda is not something to play around with.”

He cited past insurgencies in northern Uganda, adding: “In 1986, we had to clear that group… then deal with Kony, Lakwena, the cattle rustlers, and you don’t appreciate those efforts!”

A legacy under debate

Museveni’s early writings and speeches reveal a leader who once placed strict limits on the legitimacy of power and warned against life presidencies — a stance that continues to fuel debate among critics and supporters alike.

To admirers, he remains the guarantor of stability in a turbulent region. To critics, his long stay in office represents the very problem he once diagnosed.

Either way, Museveni’s own words from the 1970s and 1980s continue to echo loudly in Uganda’s political conversation — reminders of promises made at the dawn of the NRM era, and questions that still shape the country’s future.