As Uganda’s political temperature rises ahead of the 2026 general elections, one controversy has sparked debate far beyond legal technicalities and party loyalties: the disqualification of Kadongo Kamu musician and Kyengera Town Council Mayor Mathias Walukagga from the Busiro East parliamentary race by the Electoral Commission (EC).

Yet beyond the court petitions, X (formerly Twitter) arguments, and partisan outrage lies a deeper national question—what does it truly mean to be “useful” to Uganda?

Ugandan novelist, lawyer, and outspoken dissident writer Kakwenza Rukirabashaija offers a provocative answer. In a widely circulated reflection, Kakwenza argues that Walukagga’s greatest contribution to the country does not lie in Parliament, but in music.

“Mr Mathias Walukagga is more useful to Uganda as a Kadongokamu musician than he would ever be as a politician. His gift lies in naming our pain through music and poetry—enlightenment, not administering budgets and making laws.”

Kakwenza’s argument is not an attack on Walukagga as a person, nor necessarily a defence of the Electoral Commission. Rather, it is a critique of Uganda’s obsession with political office as the highest—or only—form of national service.

Beyond Parliament: Rethinking National Repair

Mathias Walukagga is no ordinary artist. For decades, Kadongo Kamu musicians have functioned as the country’s unofficial chroniclers—naming injustice, corruption, poverty, and betrayal in ways that resonate with ordinary citizens.

Walukagga belongs to this tradition: his music speaks to lived realities in markets, villages, and town councils more directly than most parliamentary speeches ever do.

Kakwenza challenges the assumption that change must flow through formal political power. “I sometimes wonder why we struggle to accept our talents and push them to their limits in the service of our country. Not every form of national repair wears a suit or sits in Parliament.”

In a country where artists, journalists, and writers have historically shaped political consciousness—often at great personal cost—the argument is difficult to dismiss. From Kadongo Kamu to protest poetry, culture has long been a vehicle of resistance and education in Uganda.

When Politics Becomes “I Also Want to Eat”

Walukagga’s political journey has not been without controversy. Currently, the Mayor of Kyengera Town Council and a National Unity Platform (NUP) flagbearer, he was recently disqualified by the EC over an expired Mature Age Entry Certificate. The decision has divided public opinion.

Supporters argue the EC acted inconsistently and overstepped its mandate, especially since Walukagga’s academic equivalence had been cleared by the National Council for Higher Education, and he is pursuing a degree. Critics, however, insist the law is clear and accuse both Walukagga and NUP of negligence.

But Kakwenza reframes the debate entirely, suggesting that politics itself often attracts the wrong motivations. “You do not need to be a politician to fix Uganda. Politics becomes attractive mostly when pennilessness and greed enter your head, when power and its inflated privileges start masquerading as patriotism.”

It is a harsh assessment, but one that resonates in a country where political office is frequently associated with wealth accumulation, immunity, and access to state resources.

Kakwenza concludes bluntly: “If everyone did what they are supposed to do—the right thing—that is the beginning of change. The rest, scampering for political positions, is called ‘I also want to eat.’”

The Walukagga Dilemma

This perspective does not deny Walukagga’s popularity or his democratic right to seek office. Nor does it absolve institutions from scrutiny. Rather, it asks whether Uganda loses something irreplaceable when its artists abandon their craft for politics.

Walukagga’s music has educated, mobilised, and comforted many Ugandans. His songs reach places where campaign manifestos never will. As a musician, he operates beyond party lines, electoral cycles, and legal technicalities. As a politician, he becomes vulnerable to paperwork, courts, and partisan warfare.

On social media, reactions reflect this tension. While many NUP supporters frame his disqualification as political persecution, others—sometimes mockingly—suggest he should “go back to school” or wait for 2031. Neutral voices emphasise that the law, however imperfect, must apply equally.

Yet Kakwenza’s intervention shifts the spotlight from legality to legacy.

Culture as a Political Force

Uganda’s history is replete with examples of cultural figures who shaped national consciousness more profoundly than elected officials. Songs, plays, novels, and poems have preserved memory, challenged power, and articulated dissent when institutions failed.

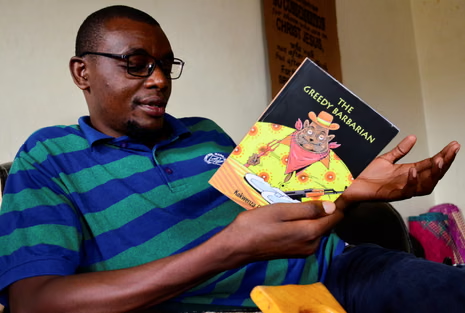

Kakwenza himself—winner of the 2021 English PEN Pinter International Writer of Courage Award and author of The Greedy Barbarian and Banana Republic: Where Writing Is Treasonous—knows this cost firsthand. His belief in cultural resistance is not theoretical; it is lived.

Seen this way, his comments about Walukagga are less an insult and more a call to radical self-awareness.

A Broader Question for Uganda

Ultimately, the Walukagga debate exposes a broader national anxiety: the belief that relevance equals political office. In a society grappling with unemployment, inequality, and shrinking civic space, politics appears as both salvation and a trap.

Kakwenza’s challenge is uncomfortable but necessary. Uganda does not only need more politicians; it needs people excelling—fearlessly and ethically—in every field.

Whether Walukagga returns to the ballot through the courts or retreats fully into music, the conversation he has ignited may outlast the election cycle.

Perhaps the most radical idea is this: Uganda can be fixed by artists, teachers, farmers, writers, and musicians—doing their work with integrity—long before Parliament ever does.